What can you do with it

The purpose of this page is to serve as an introduction to the basics of Ethereum that you will need to understand from a development standpoint, in order to produce contracts and decentralized applications. For a general introduction to Ethereum, see the white paper, and for a full technical spec see the yellow papers, although those are not prerequisites for this page; that is to say, this page is meant as an alternative introduction to Ethereum specifically targeted toward application developers.

Introduction

Ethereum is a platform that is intended to allow people to easily write decentralized applications (Đapps) using blockchain technology. A decentralized application is an application which serves some specific purpose to its users, but which has the important property that the application itself does not depend on any specific party existing. Rather than serving as a front-end for selling or providing a specific party's services, a Đapp is a tool for people and organizations on different sides of an interaction use to come together without any centralized intermediary.

Even necessary "intermediary" functions that are typically the domain of centralized providers, such as filtering, identity management, escrow and dispute resolution, are either handled directly by the network or left open for anyone to participate, using tools like internal token systems and reputation systems to ensure that users get access to high-quality services. Early examples of Đapps include BitTorrent for file sharing and Bitcoin for currency. Ethereum takes the primary developments used by BitTorrent and Bitcoin, the peer to peer network and the blockchain, and generalizes them in order to allow developers to use these technologies for any purpose.

The Ethereum blockchain can be alternately described as a blockchain with a built-in programming language, or as a consensus-based globally executed virtual machine. The part of the protocol that actually handles internal state and computation is referred to as the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM). From a practical standpoint, the EVM can be thought of as a large decentralized computer containing millions of objects, called "accounts", which have the ability to maintain an internal database, execute code and talk to each other.

There are two types of accounts:

- Externally owned account (EOAs): an account controlled by a private key, and if you own the private key associated with the EOA you have the ability to send ether and messages from it.

- Contract: an account that has its own code, and is controlled by code.

By default, the Ethereum execution environment is lifeless; nothing happens and the state of every account remains the same. However, any user can trigger an action by sending a transaction from an externally owned account, setting Ethereum's wheels in motion. If the destination of the transaction is another EOA, then the transaction may transfer some ether but otherwise does nothing. However, if the destination is a contract, then the contract in turn activates, and automatically runs its code.

The code has the ability to read/write to its own internal storage (a database mapping 32-byte keys to 32-byte values), read the storage of the received message, and send messages to other contracts, triggering their execution in turn. Once execution stops, and all sub-executions triggered by a message sent by a contract stop (this all happens in a deterministic and synchronous order, ie. a sub-call completes fully before the parent call goes any further), the execution environment halts once again, until woken by the next transaction.

Contracts generally serve four purposes:

Maintain a data store representing something which is useful to either other contracts or to the outside world; one example of this is a contract that simulates a currency, and another is a contract that records membership in a particular organization.

Serve as a sort of externally owned account with a more complicated access policy; this is called a "forwarding contract" and typically involves simply resending incoming messages to some desired destination only if certain conditions are met; for example, one can have a forwarding contract that waits until two out of a given three private keys have confirmed a particular message before resending it (ie. multisig). More complex forwarding contracts have different conditions based on the nature of the message sent; the simplest use case for this functionality is a withdrawal limit that is overrideable via some more complicated access procedure.

Manage an ongoing contract or relationship between multiple users. Examples of this include a financial contract, an escrow with some particular set of mediators, or some kind of insurance. One can also have an open contract that one party leaves open for any other party to engage with at any time; one example of this is a contract that automatically pays a bounty to whoever submits a valid solution to some mathematical problem, or proves that it is providing some computational resource.

Provide functions to other contracts; essentially serving as a software library.

Contracts interact with each other through an activity that is alternately called either "calling" or "sending messages". A "message" is an object containing some quantity of ether (a special internal currency used in Ethereum with the primary purpose of paying transaction fees), a byte-array of data of any size, the addresses of a sender and a recipient. When a contract receives a message it has the option of returning some data, which the original sender of the message can then immediately use. In this way, sending a message is exactly like calling a function.

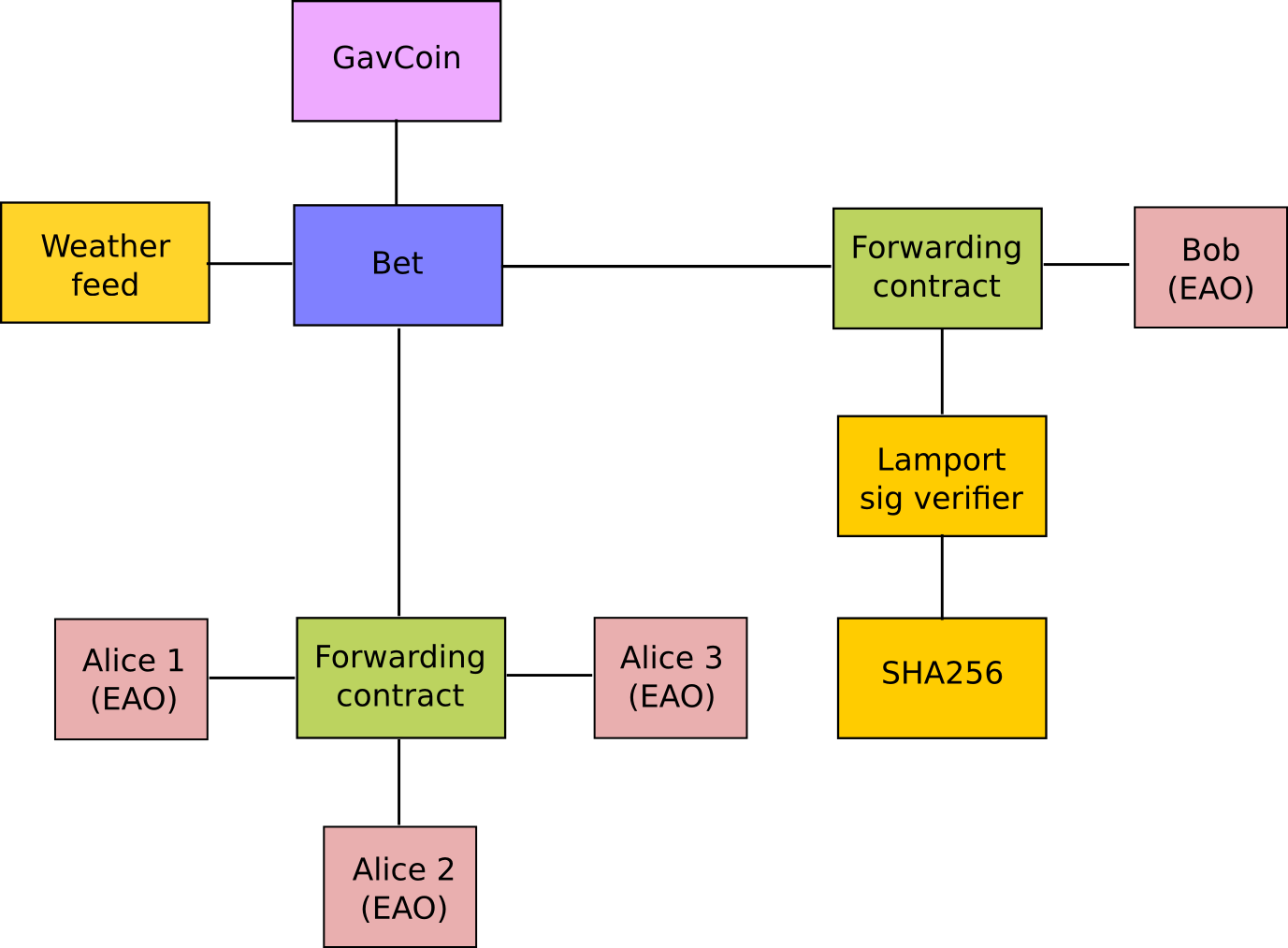

Because contracts can play such different roles, we expect that contracts will be interacting with each other. As an example, consider a situation where Alice and Bob are betting 100 GavCoin that the temperature in San Francisco will not exceed 35ºC at any point in the next year. However, Alice is very security-conscious, and as her primary account uses a forwarding contract which only sends messages with the approval of two out of three private keys. Bob is paranoid about quantum cryptography, so he uses a forwarding contract which passes along only messages that have been signed with Lamport signatures alongside traditional ECDSA (but because he's old fashioned, he prefers to use a version of Lamport sigs based on SHA256, which is not supported in Ethereum directly).

The betting contract itself needs to fetch data about the San Francisco weather from some contract, and it also needs to talk to the GavCoin contract when it wants to actually send the GavCoin to either Alice or Bob (or, more precisely, Alice or Bob's forwarding contract). We can show the relationships between the accounts thus:

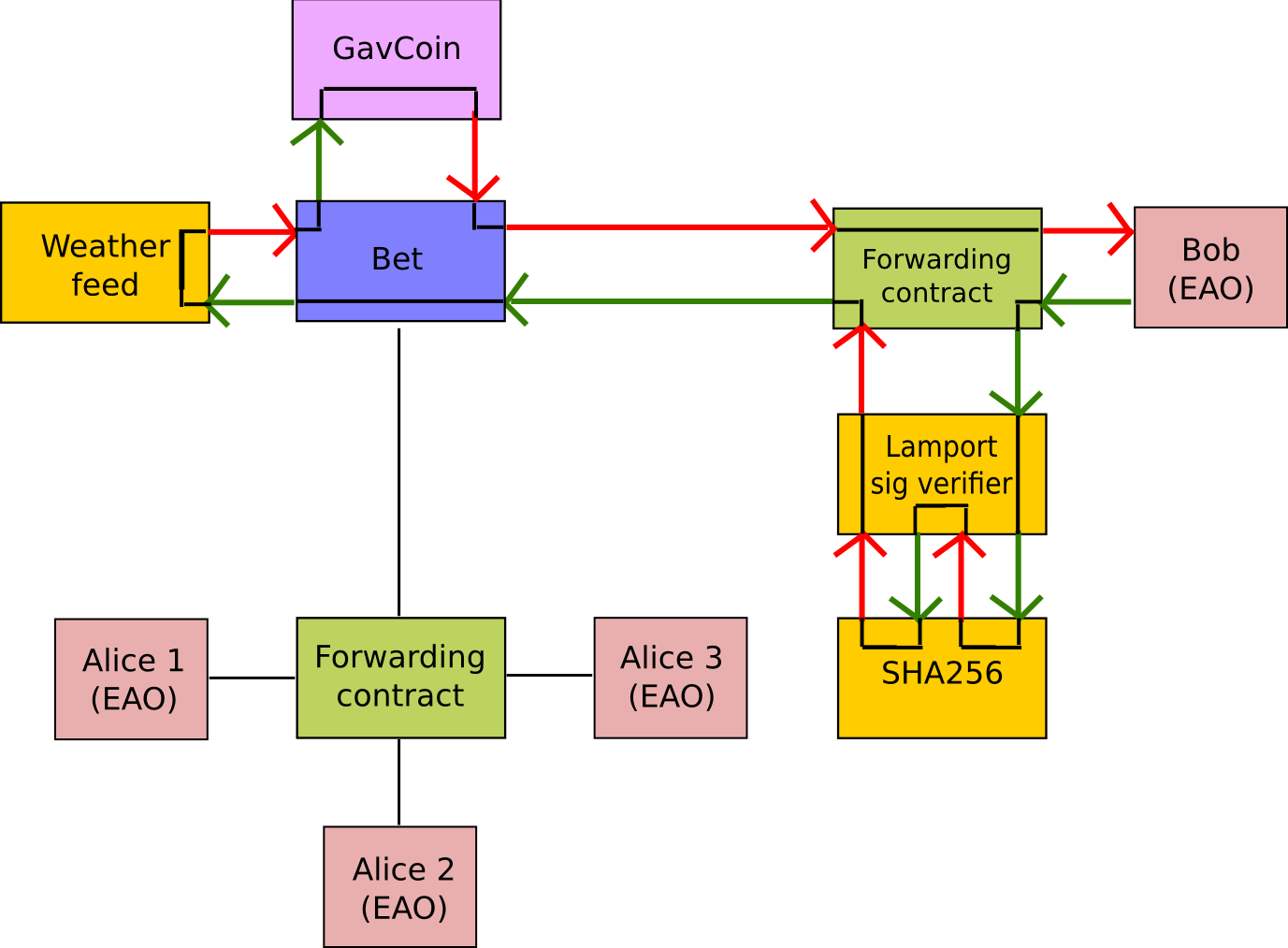

When Bob wants to finalize the bet, the following steps happen:

- A transaction is sent, triggering a message from Bob's EOA to Bob's forwarding contract.

- Bob's forwarding contract sends the hash of the message and the Lamport signature to a contract which functions as a Lamport signature verification library.

- The Lamport signature verification library sees that Bob wants a SHA256-based Lamport sig, so it calls the SHA256 library many times as needed to verify the signature.

- Once the Lamport signature verification library returns 1, signifying that the signature has been verified, it sends a message to the contract representing the bet.

- The bet contract checks the contract providing the San Francisco temperature to see what the temperature is.

- The bet contract sees that the response to the messages shows that the temperature is above 35ºC, so it sends a message to the GavCoin contract to move the GavCoin from its account to Bob's forwarding contract.

Note that the GavCoin is all "stored" as entries in the GavCoin contract's database; the word "account" in the context of step 6 simply means that there is a data entry in the GavCoin contract storage with a key for the bet contract's address and a value for its balance. After receiving this message, the GavCoin contract decreases this value by some amount and increases the value in the entry corresponding to Bob's forwarding contract's address. We can see these steps in the following diagram:

State Machine

Computation in the EVM is done using a stack-based bytecode language that is like a cross between Bitcoin Script, traditional assembly and Lisp (the Lisp part being due to the recursive message-sending functionality). A program in EVM is a sequence of opcodes, like this:

PUSH1 0 CALLDATALOAD SLOAD NOT PUSH1 9 JUMPI STOP JUMPDEST PUSH1 32 CALLDATALOAD PUSH1 0 CALLDATALOAD SSTORE

The purpose of this particular contract is to serve as a name registry; anyone can send a message containing 64 bytes of data, 32 for the key and 32 for the value. The contract checks if the key has already been registered in storage, and if it has not been then the contract registers the value at that key.

During execution, an infinitely expandable byte-array called "memory", the "program counter" pointing to the current instruction, and a stack of 32-byte values is maintained. At the start of execution, memory and stack are empty and the PC is zero. Now, let us suppose the contract with this code is being accessed for the first time, and a message is sent in with 123 wei (1018 wei = 1 ether) and 64 bytes of data where the first 32 bytes encode the number 54 and the second 32 bytes encode the number 2020202020.

Thus, the state at the start is:

PC: 0 STACK: [] MEM: [], STORAGE: {}

The instruction at position 0 is PUSH1, which pushes a one-byte value onto the stack and jumps two steps in the code. Thus, we have:

PC: 2 STACK: [0] MEM: [], STORAGE: {}

The instruction at position 2 is CALLDATALOAD, which pops one value from the stack, loads the 32 bytes of message data starting from that index, and pushes that on to the stack. Recall that the first 32 bytes here encode 54.

PC: 3 STACK: [54] MEM: [], STORAGE: {}

SLOAD pops one from the stack, and pushes the value in contract storage at that index. Since the contract is used for the first time, it has nothing there, so zero.

PC: 4 STACK: [0] MEM: [], STORAGE: {}

NOT pops one value and pushes 1 if the value is zero, else 0

PC: 5 STACK: [1] MEM: [], STORAGE: {}

Next, we PUSH1 9.

PC: 7 STACK: [1, 9] MEM: [], STORAGE: {}

The JUMPI instruction pops 2 values and jumps to the instruction designated by the first only if the second is nonzero. Here, the second is nonzero, so we jump. If the value in storage index 54 had not been zero, then the second value from top on the stack would have been 0 (due to NOT), so we would not have jumped, and we would have advanced to the STOP instruction which would have led to us stopping execution.

PC: 9 STACK: [] MEM: [], STORAGE: {}

Here, we PUSH1 32.

PC: 11 STACK: [32] MEM: [], STORAGE: {}

Now, we CALLDATALOAD again, popping 32 and pushing the bytes in message data starting from byte 32 until byte 63.

PC: 13 STACK: [2020202020] MEM: [], STORAGE: {}

Next, we PUSH1 0.

PC: 14 STACK: [2020202020, 0] MEM: [], STORAGE: {}

Now, we load message data bytes 0-31 again (loading message data is just as cheap as loading memory, so we don't bother to save it in memory)

PC: 16 STACK: [2020202020, 54] MEM: [], STORAGE: {}

Finally, we SSTORE to save the value 2020202020 in storage at index 54.

PC: 17 STACK: [] MEM: [], STORAGE: {54: 2020202020}

At index 17, there is no instruction, so we stop. If there was anything left in the stack or memory, it would be deleted, but the storage will stay and be available next time someone sends a message. Thus, if the sender of this message sends the same message again (or perhaps someone else tries to reregister 54 to 3030303030), the next time the JUMPI at position 7 would not process, and execution would STOP early at position 8.

Fortunately, you do not have to program in low-level assembly; a high-level language exists, especially designed for writing contracts, known as Solidity exists to make it much easier for you to write contracts (there are several others, too, including LLL, Serpent and Mutan, which you may find easier to learn or use depending on your experience). Any code you write in these languages gets compiled into EVM, and to create the contracts you send the transaction containing the EVM bytecode.

There are two types of transactions: a sending transaction and a contract creating transaction. A sending transaction is a standard transaction, containing a receiving address, an ether amount, a data bytearray and some other parameters, and a signature from the private key associated with the sender account. A contract creating transaction looks like a standard transaction, except the receiving address is blank. When a contract creating transaction makes its way into the blockchain, the data bytearray in the transaction is interpreted as EVM code, and the value returned by that EVM execution is taken to be the code of the new contract; hence, you can have a transaction do certain things during initialization. The address of the new contract is deterministically calculated based on the sending address and the number of times that the sending account has made a transaction before (this value, called the account nonce, is also kept for unrelated security reasons). Thus, the full code that you need to put onto the blockchain to produce the above name registry is as follows:

PUSH1 16 DUP PUSH1 12 PUSH1 0 CODECOPY PUSH1 0 RETURN STOP PUSH1 0 CALLDATALOAD SLOAD NOT PUSH1 9 JUMPI STOP PUSH1 32 CALLDATALOAD PUSH1 0 CALLDATALOAD SSTORE

The key opcodes are CODECOPY, copying the 16 bytes of code starting from byte 12 into memory starting at index 0, and RETURN, returning memory bytes 0-16, ie. code byes 12-28 (feel free to "run" the execution manually on paper to verify that those parts of the code and memory actually get copied and returned). Code bytes 12-28 are, of course, the actual code as we saw above.

Gas

One important aspect of the way the EVM works is that every single operation that is executed inside the EVM is actually simultaneously executed by every full node. This is a necessary component of the Ethereum 1.0 consensus model, and has the benefit that any contract on the EVM can call any other contract at almost zero cost, but also has the drawback that computational steps on the EVM are very expensive. Roughly, a good heuristic to use is that you will not be able to do anything on the EVM that you cannot do on a smartphone from 1999. Acceptable uses of the EVM include running business logic ("if this then that") and verifying signatures and other cryptographic objects; at the upper limit of this are applications that verify parts of other blockchains (eg. a decentralized ether-to-bitcoin exchange); unacceptable uses include using the EVM as a file storage, email or text messaging system, anything to do with graphical interfaces, and applications best suited for cloud computing like genetic algorithms, graph analysis or machine learning.

In order to prevent deliberate attacks and abuse, the Ethereum protocol charges a fee per computational step. The fee is market-based, though mandatory in practice; a floating limit on the number of operations that can be contained in a block forces even miners who can afford to include transactions at close to no cost to charge a fee commensurate with the cost of the transaction to the entire network; see the whitepaper section on fees for more details on the economic underpinnings of our fee and block operation limit system.

The way the fee works is as follows. Every transaction must contain, alongside its other data, a GASPRICE and STARTGAS value. STARTGAS is the amount of "gas" that the transaction assigns itself, and GASPRICE is the fee that the transaction pays per unit of gas; thus, when a transaction is sent, the first thing that is done during evaluation is subtracting STARTGAS * GASPRICE wei plus the transaction's value from the sending account balance. GASPRICE is set by the transaction sender, but miners will likely refuse to process transactions whose GASPRICE is too low.

Gas can be roughly thought of as a counter of computational steps, and is something that exists during transaction execution but not outside of it. When transaction execution starts, the gas remaining is set to STARTGAS - 21000 - 68 * TXDATALEN where TXDATALEN is the number of bytes in transaction data (note: zero bytes are charged only 4 gas due to the greater compressibility of long strings of zero bytes). Every computational step, a certain amount (usually 1, sometimes more depending on the operation) of gas is subtracted from the total. If gas goes down to zero, then all execution reverts, but the transaction is still valid and the sender still has to pay for gas. If transaction execution finishes with N >= 0 gas remaining, then the sending account is refunded with N * GASPRICE wei.

During contract execution, when a contract sends a message, that message call itself comes with a gas limit, and the sub-execution works the same way (namely, it can either run out of gas and revert or execute successfully and return a value). If sub-execution runs out of gas, the parent execution continues; thus, it is perfectly "safe" for a contract to call another contract if you set a gas limit on the sub-execution. If sub-execution has some gas remaining, then that gas is returned to the parent execution to continue using.

Virtual machine opcodes

A complete listing of the opcodes in the EVM can be found in the yellow paper. Note that high-level languages will often have their own wrappers for these opcodes, sometimes with very different interfaces.

Basics of the Ethereum Blockchain

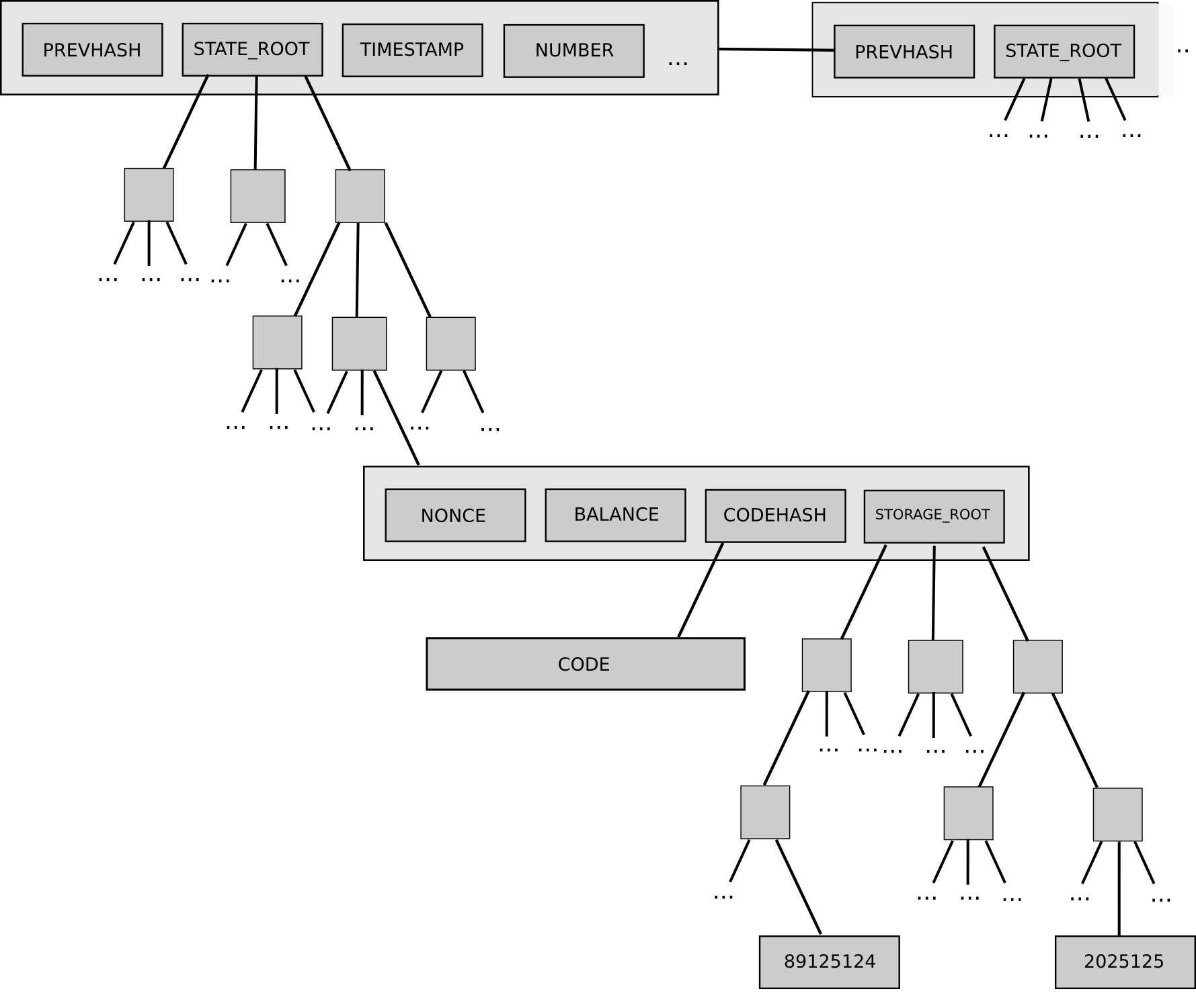

The Ethereum blockchain (or "ledger") is the decentralized, massively replicated database in which the current state of all accounts is stored. The blockchain uses a database called a Patricia tree (or "trie") to store all accounts; this is essentially a specialized kind of Merkle tree that acts as a generic key/value store. Like a standard Merkle tree, a Patricia tree has a "root hash" that can be used to refer to the entire tree, and the contents of the tree cannot be modified without changing the root hash. For each account, the tree stores a 4-tuple containing [account_nonce, ether_balance, code_hash, storage_root], where account_nonce is the number of transactions sent from the account (kept to prevent replay attacks), ether_balance is the balance of the account, code_hash the hash of the code if the account is a contract and "" otherwise, and storage_root is the root of yet another Patricia tree which stores the storage data.

Every minute, a miner produces a new block (the concept of mining in Ethereum is exactly the same as in Bitcoin; see any Bitcoin tutorial for more info on this), and that block contains a list of transactions that happened since the last block and the root hash of the Patricia tree representing the new state ("state tree") after applying those transactions and giving the miner an ether reward for creating the block.

Because of the way the Patricia tree works, if few changes are made then most parts of the tree will be exactly the same as in the last block; hence, there is no need to store data twice as nodes in the new tree will simply be able to point back to the same memory address that stores the nodes of the old tree in places where the new tree and the old tree are exactly the same. If a thousand pieces of data are changed between block N and block N + 1, even if the total size of the tree is many gigabytes, the amount of new data that needs to be stored for block N + 1 is at most a few hundred kilobytes and often substantially less (especially if multiple changes happen inside the same contract). Every block contains the hash of the previous block (this is what makes the block set a "chain") as well as ancillary data like the block number, timestamp, address of the miner and gas limit.

Graphical Interfaces

A contract by itself is a powerful thing, but it is not a complete Đapp. A Đapp, rather, is defined as a combination of a contract and a graphical interface for using that contract (note: this is only true for now; future versions of Ethereum will include whisper, a protocol for allowing nodes in a Đapp to send direct peer-to-peer messages to each other without the blockchain). Right now, the interface is implemented as an HTML/CSS/JS webpage, with a special Javascript API in the form of the eth object for working with the Ethereum blockchain. The key parts of the Javascript API are as follows:

eth.transact(from, ethervalue, to, data, gaslimit, gasprice)- sends a transaction to the desired address from the desired address (note:frommust be a private key andtomust be an address in hex form) with the desired parameters(string).pad(n)- converts a number, encoded as a string, to binary formnbytes longeth.gasPrice- returns the current gas priceeth.secretToAddress(key)- converts a private key into an addresseth.storageAt(acct, index)- returns the desired account's storage entry at the desired indexeth.key- the user's private keyeth.watch(acct, index, f)- callsfwhen the given storage entry of the given account changes

You do not need any special source file or library to use the eth object; however, your Đapp will only work when opened in an Ethereum client, not a regular web browser. For an example of the Javascript API being used in practice, see the source code of this webpage.